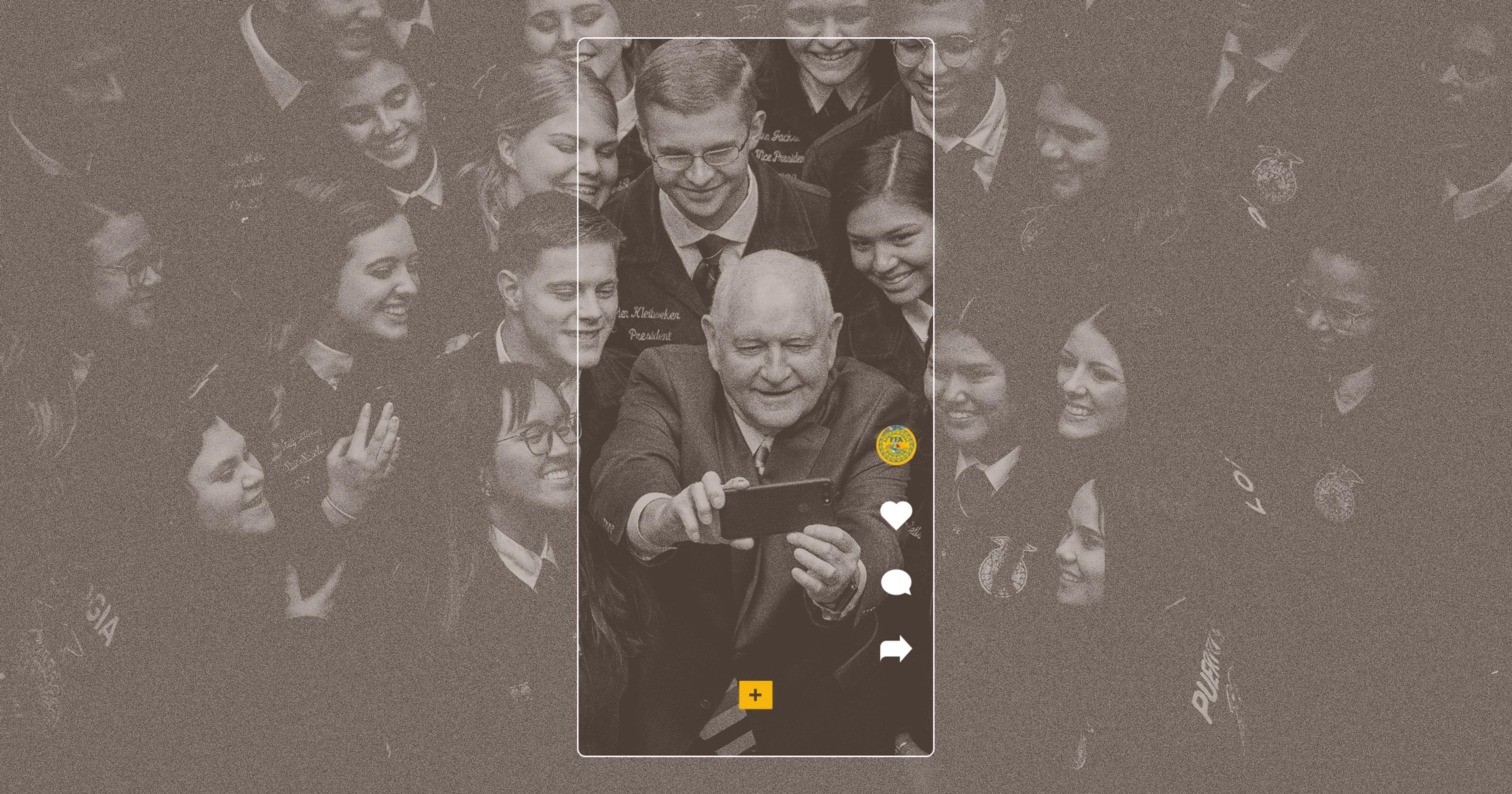

In contrast to its old-fashioned reputation, today’s FFA members utilize cutting-edge technologies to address agriculture’s most pressing challenges.

Stephenville High School senior and FFA (formerly Future Farmers of America) member Charleigh Feuerbacher does not come from a traditional farming background. Her father is a landscaper and her mother works for the government of their central Texas town. But growing up surrounded by farms and her father’s plants, she developed an interest in horticulture.

So when Feuerbacher took Principles of Agriculture as a freshman, she was immediately drawn to the school greenhouse and its hydroponics operation. The 10 soilless growing systems were constructed for less than $30 a piece, using a dark plastic tub and aquarium airline pumps and oxygen stones. “I’m very passionate about the real world effects that these systems have,” she said.

Encouraged by her FFA advisor Savannah Bowers, Feuerbacher decided to do a Supervised Agricultural Experience (SAE), a work-based learning project overseen by a teacher, focused on hydroponics research. The studies she completed — testing the effect of different sugar additives on plant growth and how best to increase the Vitamin C content of greens — earned her the national Proficiency Award in the category of Agricultural Research - Plant Sciences at the FFA National Convention last November.

Feuerbacher’s highly technical, lab-based SAE is a long way from modern stereotypes about FFA — think Napoleon Dynamite taste testing milk. “Kids are raising pigs and sheep and steers and getting their blue ribbons for corn,” acknowledged national program specialist Brett Evans. “But there’s a whole lot more.”

According to Evans and his colleague Madeline Young, the National FFA Organization is continually updating its programming to meet the technological advances, challenges, and opportunities facing 21st-century agriculture. Whether broadening SAE categories or taking steps to attract urban students and students of color, Evans and Young said that the organization is working to ensure it stays relevant and helps grow the nation’s agricultural workforce.

So far, the efforts seem to be paying off. Membership grew 11% in 2023 alone, to nearly 950,000 students. “We’re about to break a million members,” Evans said of the organization. “It’s more important than it’s ever been.”

Growth Areas

Even a brief skim of the 2023 National Proficiency Award winners’ projects demonstrate that today’s FFA students are doing innovative, cutting-edge work that engages with all the latest technology. They are founding their own genetics labs to test ruminant blood for pregnancy, creating podcasts to interview agricultural leaders, flying drones, and breeding hypoallergenic Yorkie Poodles (aka Yorkie-Poos).

To ensure that its Proficiency Awards reflect growing trends in agriculture, FFA’s committees regularly review and update the award’s categories. “Social media has played a huge factor in the things that students are being influenced to do or to try,” said Young. Some of those trends are decidedly old school: “Right now, there’s a huge craze in homesteading,” she said.

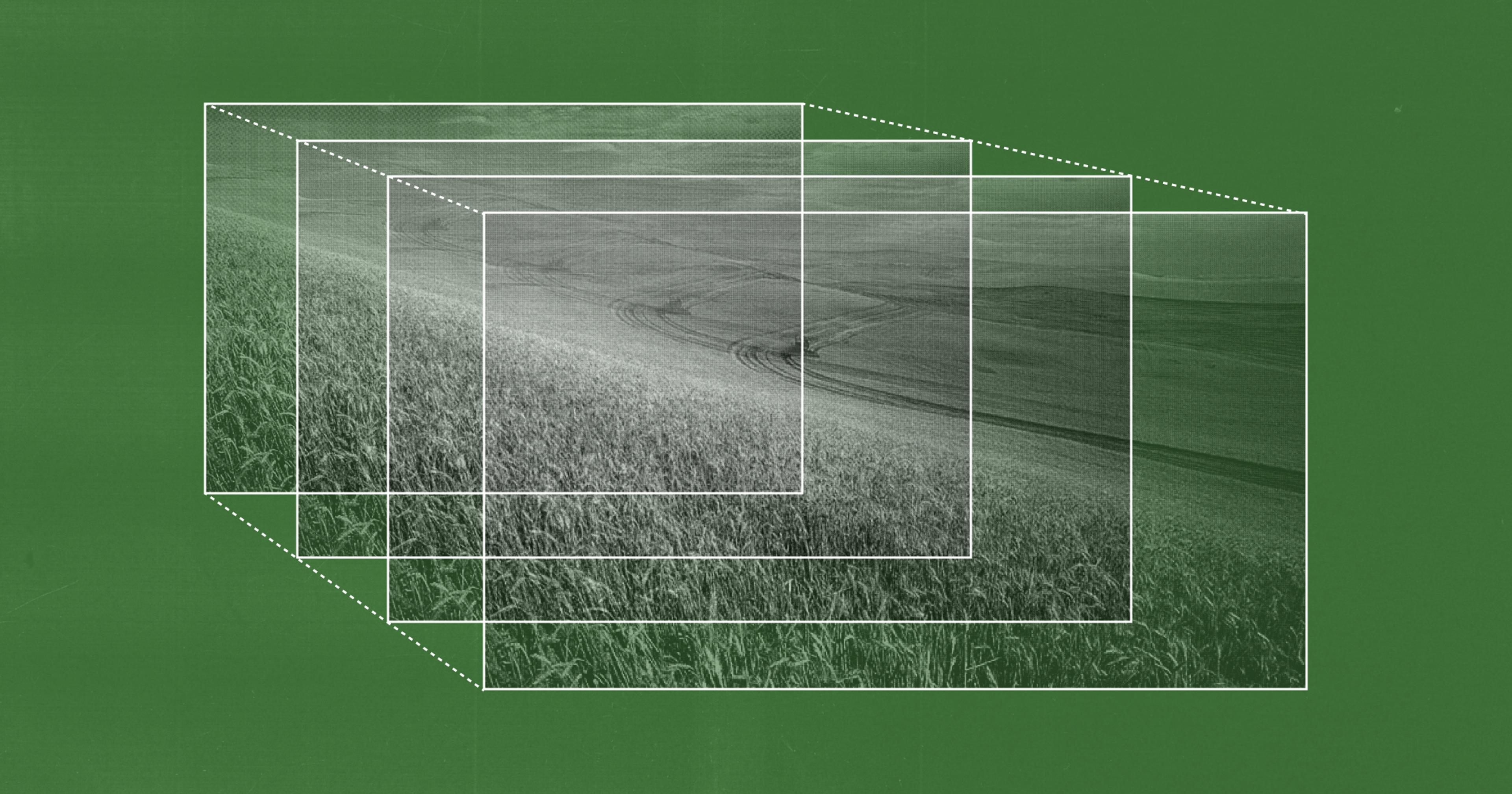

One effect of this emphasis on growing your own food, said Evans, is an increase in diversification. On the production side, that could mean a student growing vegetables and raising a couple of cows, whereas a student with a research SAE might want to design multiple studies looking at animals, plants, and machines.

As consumers have become more anxious about the global food supply chain in the wake of pandemic shortages and food recalls, Young said that students are also designing SAEs around foodborne illnesses and even food labeling. She recently read an SAE application from a student comparing consumer impressions of different gluten-free baked goods in terms of taste, texture, and composition.

They are founding their own genetics labs to test ruminant blood for pregnancy, creating podcasts to interview agricultural leaders, flying drones, and breeding hypoallergenic Yorkie Poodles (aka Yorkie-Poos).

Evans noted a rise in SAEs focused on value-added products, a topic that inspired intense debate in his project committee. “If you grow apples, that’s agriculture. If you market apples, that’s agriculture. If you pick apples, clean them, put a sticker on them, and ship them to the grocery store … agriculture, or something else?” They have not decided yet whether to add canning and food preservation as new SAE categories.

It’s also clear that some of last year’s national Proficiency Award winners consider things highly technological that others may consider simplistic. When asked about the role of technology in his award-winning Specialty Crop Production project, for instance, North Huron FFA member Noah Koth doesn’t start with the precision agriculture class he is currently taking as a college freshman.

Instead, this fourth-generation farmer sees the real technology in the sugar beets and turtle black beans that his family plants, harvests, and transports on 1,200 acres in Kinde, Michigan. “Plants almost have their own computer system,” Koth told Ambrook Research. “If they’re dry, they’ll shrivel up their leaves so that sunlight is hitting less of the area of the leaf.”

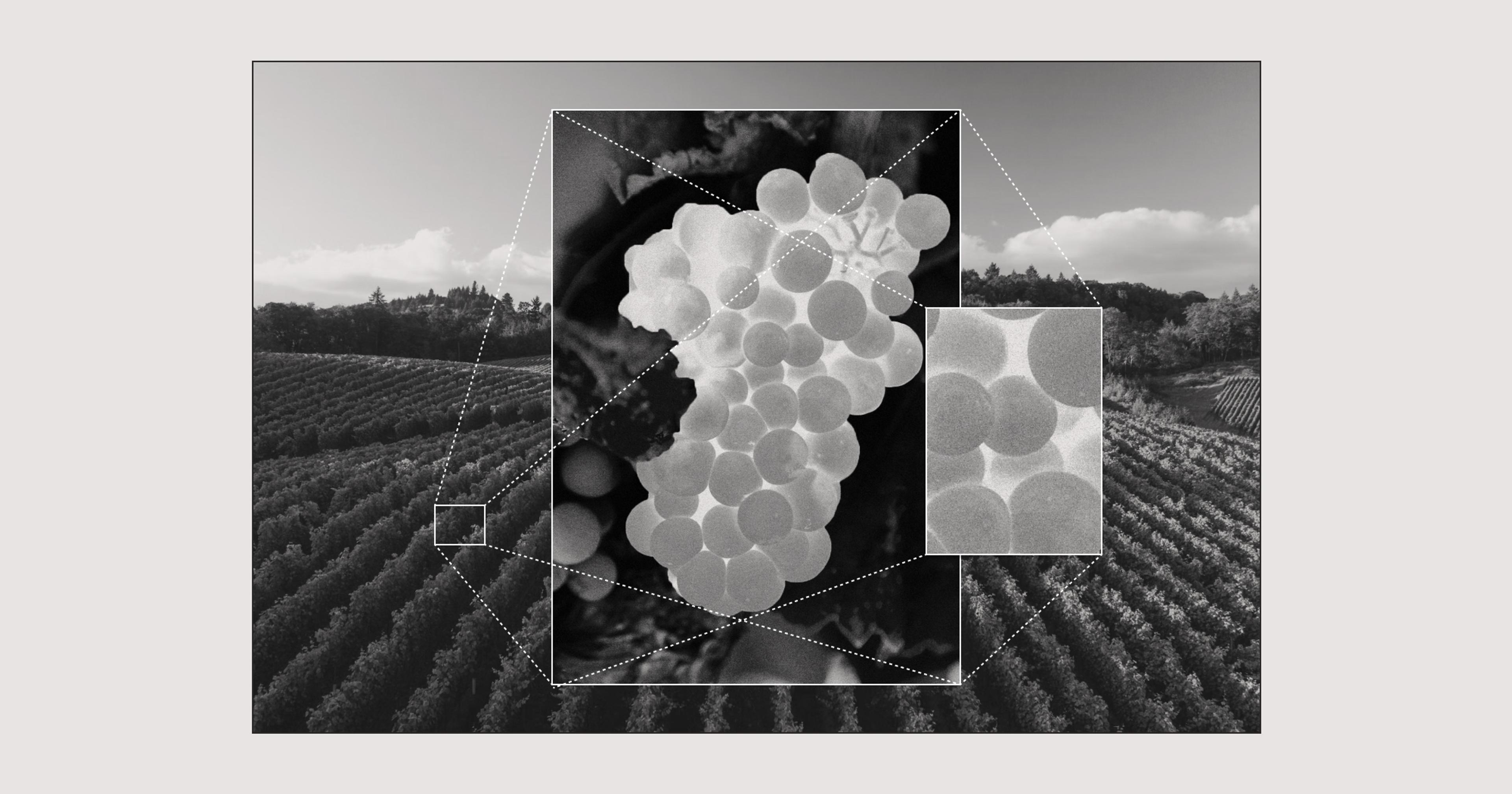

Similarly, Clancey Krahn, last year’s winner in the National Proficiency Award in the Dairy Production - Entrepreneurship category, considers one of the most modern aspects of her family’s five-acre dairy farm in Oregon to be its complete vertical integration — a self-sufficiency common before processing facilities became concentrated among a few large corporations. “We do everything from birthing baby calves, to processing milk, to shipping your milk, all on one property,” she said.

Krahn uses SenseHub monitoring technology to track her cows’ rumination and heat cycles, but the most innovative decisions during her SAE had everything to do with resilience and adaptability. During the online-only education phase of the pandemic, Krahn learned her school might shut down its agricultural program, so she transferred to Scio High School.

“She has a drive and a desire to do well and succeed, as well as a passion for agriculture and the dairy industry that I think is very rare to come by,” said Krysta Sprague, Krahn’s teacher and FFA advisor at Scio.

Diversifying Both People and Projects

Another way that Evans and Young are trying to ensure the ongoing relevance of FFA is to better support non-rural chapters and FFA members of color. When it comes to evaluating SAEs, Evans said, “we are trying very hard to start kids off on a level playing field.”

Even so, none of last year’s four American Star Award or national Proficiency Award winners came from an urban chapter.

“I was surrounded by rural America. So that was what our ag program was,” said former National FFA President Bre Holbert of her experience in high school as a non-traditional agriculture student and FFA member in the city of Lodi, California. Since her school’s SAE pathways prioritized projects suited to students with a rural background, Holbert found it easier to focus on leadership development events like public speaking. This path eventually led her to become the first female African-American national president in 2018.

Holbert now teaches agriculture and is an FFA advisor at Florin High School, a suburban-urban chapter 20 minutes from downtown Sacramento. With over 70 languages spoken, the school has a number of immigrant students still learning English, “which makes FFA a little hard because I think there’s a lot of language barriers to a lot of the contests,” said Holbert.

Given these barriers, Florin’s Ag Academy focuses more on SAEs than public speaking events. To meet the skills and resources of a non-rural student body, the curriculum also emphasizes co-ops, or group projects, that allow students to pool their knowledge. Current co-ops include making and selling goat milk soap, selling eggs, and raising animals to show at fairs.

Then there’s Florin’s drone team, headed by captain Honest Lee, a senior who made it to state finals this year with his SAE project. “Since drones being implemented in agriculture might be a bit foreign to many students, they might be a bit afraid to use it,” he said. “Being able to talk about my project and what I do might have inspired a few students.”

Lee’s SAE involves three major components: performing pre- and post-flight maintenance on the school’s DJI Mavic 2 drones, overseeing flight missions, and providing mapping and photography, primarily for the state’s SLEWS program, which pairs high school students with habitat restoration projects. Lee and his team members have mapped irrigation lines and checked on the status of mulch and native plants.

“We are trying very hard to start kids off on a level playing field.”

A first-generation American whose parents grew up around farmland in the highlands of Laos, Lee wants people to know that agriculture is so much more than farming. For him, this principle encompasses not only his drone project but also the public speaking and leadership experience he gained. “This experience has taught me more how to speak out with passion,” he said.

While Lee made it to the state finals, Holbert acknowledged that Florin’s students rarely become national finalists. With an FFA chapter of 700 students, “we don’t have time here to really sit down with the kids” and help them with applications, Holbert said.

Patrycja Zbrzezny, assistant principal and director of John Bowne High School’s agriculture program in Queens, also cited this issue. Plus, in an inner-city school where at least 75% of students receive educational assistance, affording the trip to the national convention in Indianapolis is itself often a deterrent, she said.

Zbrzezny — herself a graduate of the program in 2006 — prioritizes breadth over depth with her non-traditional students: “We try to open up the world of ag to them to experience it all.” The school’s 3.9-acre farm includes miniature horses, goats, and sheep, as well as 150 laying hens whose eggs the students sell at their agricultural stand. Two acres are for crop production, and their orchard grows 11 varieties of apple. There are hydroponics and aquaponics systems, and rodent, reptile, and amphibian, and exotic animal labs. Students learn agricultural mechanics at the tractor shed, and this spring will see the addition of beehives.

For their SAEs, the program’s 500-600 students work in a variety of non-traditional spaces, from veterinary offices and zoos, parks and botanical gardens, and university labs. Zbrzezny also encourages students to pursue policy-focused SAEs, working with nonprofits like GrowNYC or the recently established Office of Urban Agriculture.

The students may not produce as many award-winning SAEs as better-funded and more rural chapters, but the impact of the program is undeniable. John Bowne’s FFA graduation rates are regularly around 90%: the best out of all the programs in the 3,000-student school, which also has STEM, arts, law, computer science, and health tracks. Each year, the program receives approximately 1,000 applicants for 150 spots; most come from Queens, with some from Brooklyn and even the Bronx. Approximately half of the students are Hispanic, followed in size by African-American, Asian, white, and multiracial students.

Zbrzezny estimates that approximately 80% of their graduates who go on to college pursue degrees related to agriculture. She regularly has alumni come back to share their journey, “to show our students that it is possible for them to get there, too.”

The Future of FFA

According to Evans and Young, the most important factor in shaping a successful SAE is the passion and support of a good teacher. And that is also the biggest challenge the organization faces. “The number one problem we have is not enough teachers,” said Evans. “We have schools that want to open programs, but we are not producing enough teachers to meet the demand.” Of the teachers that are available, he added, not enough are teachers of color.

For Holbert, it’s also important to ensure white teachers are open to non-traditional ways of approaching agriculture, FFA chapter activities, and SAEs. “I came into a time where the organization was moving towards celebrating more diverse spaces and becoming more inclusive,” she said of her time as national president. Yet more than 75% of FFA’s 950,000 current student members are white.

Even with these barriers, Holbert finds that many of her students thrive doing the hands-on work of Florin’s agricultural program. “I’ve seen students that have planted a seed for the first time who do not do not speak a lick of English,” she said. “And they’ve been able to bring it in class and put their name on it, and they were so happy to take it home.”